Vincent van Gogh: The Troubled Master of Color

When you see van Gogh’s swirling, vibrant paintings, you’re looking at the work of someone who battled severe mental illness for much of his adult life. Most likely Van Gogh suffered from comorbid illnesses. Since young adulthood, he likely developed a (probably bipolar) mood disorder in combination with (traits of) a borderline personality disorder as underlying vulnerability. Arguably one of the most famous examples of an artist who experienced public challenges with mental illness, most experts agree that van Gogh lived with psychosis in some form. But psychosis is a symptom of other disorders, not a diagnosis in itself. His symptoms began after a devastating rejection from his landlord’s daughter when he was just 20 years old. After she declined his marriage proposal, he had his first psychotic break, which caused him to change his entire life in order to devote it to God. This setback at age 20 certainly marked a first step in the downwards spiral representing his health, which would lead to his suicide in 1890. The famous ear-cutting incident wasn’t just artistic eccentricity – it was a clear sign of his deteriorating mental state.

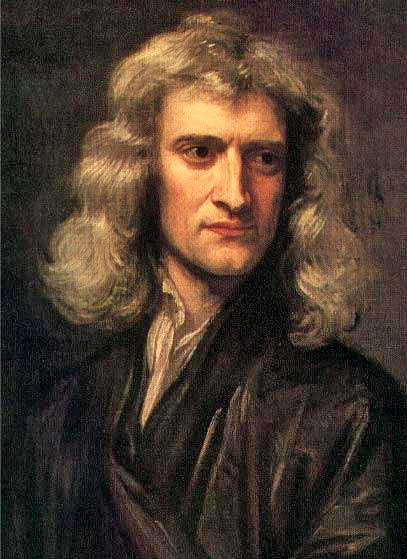

Isaac Newton: When Genius Meets Paranoia

One of the greatest scientists of all time is also the hardest genius to diagnose, but historians agree he had a lot going on. Newton suffered from huge ups and downs in his moods, indicating bipolar disorder, combined with psychotic tendencies. His inability to connect with people could place him on the autism spectrum. He also had a tendency to write letters filled with mad delusions, which some medical historians feel strongly indicates schizophrenia. Newton’s obsessions weren’t limited to physics and mathematics – Newton was so obsessed with cleanliness that he would often wash his hands dozens of times a day. He was also known to be a perfectionist, which likely contribute to his OCD. Think about it: the man who discovered gravity was so lost in his thoughts that an account describes Newton journeying all the way home without realizing he had left his horse behind; he was engrossed in a book the entire way back. This level of detachment from reality went far beyond simple absent-mindedness.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Music from the Depths of Despair

Contemporary reports in The New England Journal of Medicine and The British Journal of Psychiatry now suggest that German composer Ludwig van Beethoven suffered from bipolar disorder. These journals even suggest that one can hear Beethoven’s dramatic swings from suicidal depression to frenzied mania in the dramatic swings in dynamics and tempo in the man’s music. Beethoven’s fits of mania were well known in his circle of friends, and when he was on a high he could compose numerous works at once. It was during his down periods that many of his most celebrated works were written. Sadly, that was also when he contemplated suicide, as he told his brothers in letters throughout his life. His friends watched in horror during the early part of 1813 he went through such a depressive period that he stopped caring about his appearance, and would fly into rages during dinner parties. He also stopped composing almost completely during that time. The beauty of his Ninth Symphony emerged from a mind constantly battling its own demons.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Hidden Struggles Behind Musical Perfection

Mozart’s story is more complex than many realize. He created some of the most sophisticated music ever written, yet is also well-known for some of the most vulgar scatology you’ll ever read. Indeed, many now know that the letters, biographies, and unofficial compositions of Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are filled with references to feces, buttocks, and the like. And what some medical journals have now suggested is that these vulgar preoccupations — along with his vocal and motor tics — indicate that Mozart had Tourette’s syndrome. Mozart was known for his repetitive movements, sensitivity to noise, and poor social skills, leading some experts to conclude that he was on the autism spectrum. His musical genius coexisted with behaviors that would’ve seemed bizarre to his contemporaries – imagine the confusion of watching someone create perfect symphonies while exhibiting uncontrollable tics and obsessions.

Nikola Tesla: The Inventor’s Obsessive Mind

Nikola Tesla was often mentally compromised, though his exact condition remains debatable among historians. During Tesla’s career, however, he was either labeled “eccentric” or “insane.” Tesla’s daily struggle with abnormal behavior serves as a textbook example of using the evidence available to retroactively diagnose a mental disorder with the help of modern research and understanding. His obsessive behaviors were legendary – he had to count his steps when walking, needed exactly 18 napkins at every meal, and was terrified of germs to an extreme degree. Tesla’s mind, capable of visualizing complex electrical systems in perfect detail, was also trapped by compulsions that controlled his daily life. The same brain that revolutionized electricity couldn’t escape the prison of its own obsessive patterns.

Charles Darwin: Panic in the Face of Evolution

The father of evolutionary theory lived with crippling anxiety that nearly derailed his groundbreaking work. Darwin, one of the world’s most prominent biologists, exhibited the symptoms of panic disorder, which culminated in severe panic attacks that included heart palpitations, excessive crying, feelings of impending doom and hysterical crying. One of the symptoms of panic disorder in the DSM is concern over future attacks and significant changes in behavior related to them. Darwin fulfilled both of these criteria by refusing to leave his house later in his life and turning down speaking engagements for fear of his heart palpitations. It’s almost tragic to think that the man who explained how species adapt to survive was himself struggling to adapt to his own mental health challenges. His panic attacks were so severe that he became a virtual recluse, conducting his revolutionary science from the safety of his home while his mind waged war against him.

Edvard Munch: Painting His Inner Turmoil

The famous Norwegian painter similarly lived through bouts of depression that he called his “sufferings.” These bouts, followed by manic periods similar to Beethoven’s, were described in diary entries and influenced his modern day diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Munch also experienced auditory and visual hallucinations, which contributed to a diagnosis of psychotic disorder, in this case due to his other medical disorder rather than substance abuse. In fact, he wrote that his most famous painting, “The Scream,” was inspired by a visual hallucination he had while walking down the road with his friends. Think about that for a moment – one of the most recognizable artworks in history came directly from a hallucination. Munch literally painted his madness, creating something that resonated with people worldwide because it captured the universal experience of psychological anguish.

Kurt Gödel: Mathematical Genius Trapped by Paranoia

Gödel was a brilliant logician and mathematician, as well as a contemporary and great friend of Albert Einstein. Gödel, on the other hand, thought that someone was out to poison him. He was so sure of this delusion, especially later in life, that he would only eat food that his wife had cooked, and usually made her taste it first, just to be sure. When his wife was hospitalized for six months, Gödel stopped eating and starved to death. Here was a man who could solve complex mathematical problems that challenged the foundations of logic itself, yet he couldn’t overcome the false belief that people were trying to poison him. His paranoia became so consuming that it literally killed him – a brilliant mind destroyed by its own distorted perceptions.

Virginia Woolf: Literary Genius Drowning in Depression

English author Virginia Woolf’s battles with severe depression and bipolar disorder are well documented in both biographic and medical literature from the The American Journal of Psychiatry and elsewhere. According to the journal, Woolf “experienced mood swings from severe depression to manic excitement and episodes of psychosis,” all of which landed her in an institution for a time and informed her bouts of suicidal thoughts. Her writing, revolutionary in its stream-of-consciousness style, may have been her way of trying to make sense of her chaotic inner world. Tragically, she ultimately lost her battle with mental illness, walking into the River Ouse with her pockets filled with stones. Her final note to her husband spoke of the “terrible thing” approaching – a haunting description of how depression can feel like an unstoppable force.

Ernest Hemingway: The Writer’s Dark Battles

Hemingway’s tough-guy persona masked a lifetime of psychological struggles that eventually consumed him. His depression, paranoia, and alcoholism formed a toxic combination that shadowed his literary success. References to famous, emotionally disturbed artists, writers, poets, composers, scientists and philosophers – Vincent Van Gogh, Franz Kafka, Edward Munch, Ezra Pound, Delmore Schwartz, William Cowper, Ernest Hemingway, Friedrich Nietzsche, Eugene O’Neill, Charles Darwin, Fyodor Dostoievsky, Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath and others are cited widely in the literature. His writing style – spare, direct, emotionally restrained – might have been his way of controlling the chaos in his mind. But control was something Hemingway ultimately lost, ending his life with a shotgun in 1961, just like his father had done decades earlier.

John Nash: A Beautiful Mind Fractured by Schizophrenia

The Nobel Prize-winning mathematician’s battle with schizophrenia became famous through the movie “A Beautiful Mind,” but the reality was even more harrowing than Hollywood portrayed. Nash’s delusions were so convincing that he believed he was receiving coded messages from foreign governments through newspaper headlines. The documentary includes details of Nash’s life that A Beautiful Mind (the movie) omitted, while validating the essential authenticity of Ron Howard’s work. It also promises to provoke further national debate about mental illness, science, stigma, treatment and recovery. What’s remarkable is that Nash eventually learned to recognize his delusions without medication, essentially teaching himself to distinguish between mathematical reality and the false reality his illness created. His recovery, though incomplete, shows how even severe mental illness doesn’t have to mean the end of intellectual achievement.

Winston Churchill: The Black Dog of Leadership

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill referred to his recurring bouts with depression as his “black dog.” But his physician, Lord Moran, took note of Churchill’s depression — as well as his mania, suicidal thoughts, and sleeplessness — and made a more official diagnosis: bipolar disorder. Churchill’s ability to lead Britain through World War II while battling his own mental demons is extraordinary. His famous speeches, filled with defiant optimism, were delivered by a man who privately struggled with thoughts of suicide and overwhelming despair. He once said that he never stood near the edge of a train platform because he feared he might impulsively jump – a chilling glimpse into the mind of one of history’s greatest leaders.

The Modern Understanding: Why Genius and Madness Intersect

In a 2015 study, Iceland scientists found that people in creative professions are 25% more likely to have gene variants that increase the risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, with decode Genetics co-founder Kári Stefánsson saying, “Often, when people are creating something new, they end up straddling between sanity and insanity. I think these results support the concept of the mad genius.” Research by another panelist, James Fallon, a neurobiologist at the University of California-Irvine, suggests an answer. “People with bipolar tend to be creative when they’re coming out of deep depression,” Fallon said. When a bipolar patient’s mood improves, his brain activity shifts, too: activity dies down in the lower part of a brain region called the frontal lobe, and flares up in a higher part of that lobe. Amazingly, the very same shift happens when people have bouts of creativity. “There [is] this nexus between these circuits that have to do with bipolar and creativity,” Fallon said. Recent research suggests a far more nuanced picture. While certain mental health conditions can influence creative thinking, it’s neither a prerequisite for artistry nor an automatic barrier to success. In fact, many creatives thrive without any diagnosable illness, and those who do face mental health challenges are finding new ways to cope and create. The connection isn’t simple cause and effect – it’s more like a complex dance between brain chemistry, life experiences, and the relentless drive to create something meaningful from chaos.

What strikes you most about this tragic parade of brilliant minds? Perhaps it’s the realization that genius and suffering aren’t romantically linked – they’re often locked in a brutal struggle where creativity becomes both escape and expression of pain.