Robert Smalls: The Enslaved Man Who Commandeered a Confederate Ship

Picture this: a 23-year-old enslaved man steals a Confederate warship in broad daylight and sails his family to freedom. That’s exactly what Robert Smalls did in May 1862 when he commandeered the CSS Planter in Charleston Harbor. Smalls had been forced to work as a pilot on the vessel, but he used his knowledge of Confederate naval signals to navigate past five Southern forts. He then sailed the ship directly to the Union blockade, delivering not just his freedom but also valuable intelligence about Confederate coastal defenses. After the war, Smalls became a successful businessman and served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, yet most Americans have never heard his name.

Mary Edwards Walker: The Only Woman to Receive the Medal of Honor

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker remains the only woman in American history to receive the Medal of Honor, awarded for her service as a surgeon during the Civil War. Despite facing constant discrimination from male colleagues who refused to accept a female doctor, Walker performed surgeries on battlefields and was eventually captured by Confederate forces in 1864. She spent four months as a prisoner of war before being exchanged for a Confederate officer. Walker was a fierce advocate for women’s rights throughout her life, often wearing men’s clothing as a form of protest against restrictive women’s fashion. According to the National Archives, her Medal of Honor was controversially revoked in 1917 but restored by President Jimmy Carter in 1977, though she had refused to return it during her lifetime.

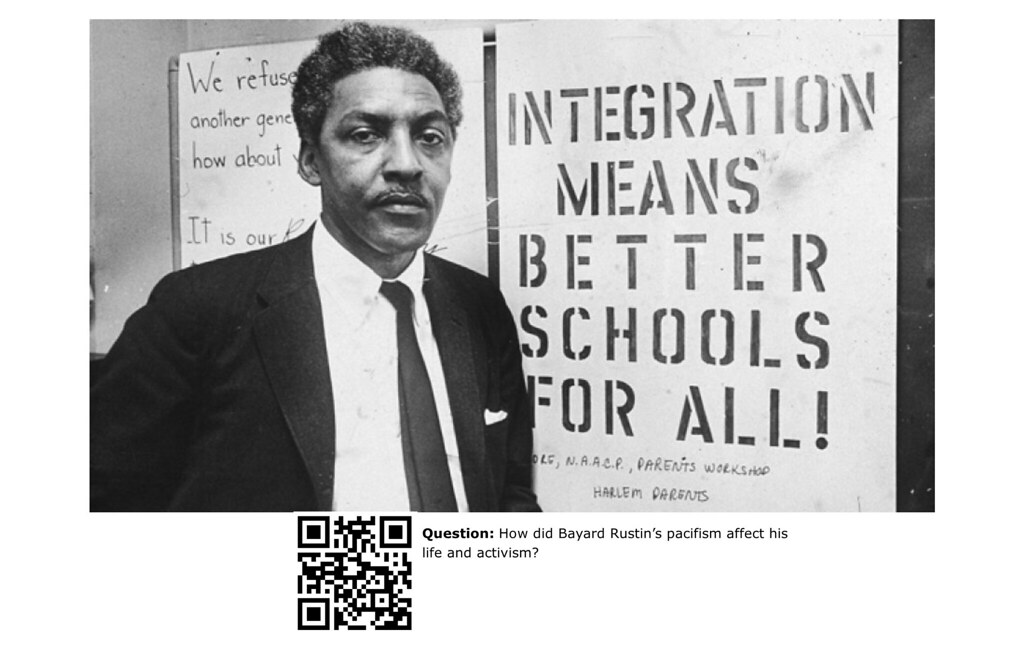

Bayard Rustin: The Architect of the March on Washington

While Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, it was Bayard Rustin who masterminded the entire March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Rustin organized the logistics for bringing 250,000 people to the nation’s capital in just eight weeks, coordinating everything from transportation to portable toilets. His expertise in nonviolent protest tactics, learned from studying Gandhi’s methods in India, became the foundation for the civil rights movement’s peaceful approach. Despite his crucial contributions, Rustin often remained in the background due to his homosexuality and former communist ties, which civil rights leaders feared would be used against the movement. Recent scholarship from the Smithsonian Institution highlights how Rustin’s strategic brilliance shaped nearly every major civil rights demonstration of the 1960s.

Frances Perkins: The Woman Who Created Social Security

Frances Perkins became the first woman to serve in a presidential cabinet when Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed her Secretary of Labor in 1933. She essentially created the modern American social safety net, drafting and championing the Social Security Act of 1935 that still protects millions of Americans today. Perkins also established the first federal minimum wage laws and helped create unemployment insurance, fundamentally reshaping how America cares for its workers. Her work extended beyond policy as she investigated the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, which killed 146 workers and sparked major workplace safety reforms. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, Perkins served for 12 years, longer than any other Labor Secretary, yet polls consistently show that fewer than 30% of Americans can identify her contributions to modern worker protections.

Sybil Ludington: The Female Paul Revere Who Rode Twice as Far

While Paul Revere’s midnight ride covered about 12 miles, 16-year-old Sybil Ludington rode nearly 40 miles through the Connecticut countryside in April 1777 to warn colonial forces of a British attack. Unlike Revere, who was captured partway through his journey, Ludington successfully completed her mission and helped rally 400 militia members to defend Danbury, Connecticut. She rode alone through dangerous terrain filled with British sympathizers and outlaws, using a stick to bang on doors and shout warnings. Her father, Colonel Henry Ludington, had sent her because she knew the winding back roads better than his soldiers. The Daughters of the American Revolution erected a statue in her honor in 1961, but most history textbooks still omit her story entirely.

Ernest Everett Just: The Biologist Who Revolutionized Cell Research

Dr. Ernest Everett Just made groundbreaking discoveries about cell biology and fertilization that laid the foundation for modern reproductive medicine. Despite facing severe racial discrimination that limited his research opportunities in the United States, Just published over 70 scientific papers and earned international recognition for his work on cell membrane function. He spent much of his career working in European laboratories, particularly in Italy and Germany, where he could conduct research without racial barriers. Just’s research on egg fertilization helped scientists understand fundamental processes of life and development, contributing to advances that would later enable in vitro fertilization. According to the National Academy of Sciences, Just was elected to prestigious international scientific societies, yet he was never offered a position at a major American research university due to his race.

Clara Lemlich: The Young Immigrant Who Sparked the Largest Strike by Women

At just 23 years old, Clara Lemlich stood up at a union meeting in 1909 and delivered a fiery speech in Yiddish that launched the “Uprising of 20,000,” the largest strike by women in American history. This Ukrainian immigrant had already been beaten by company thugs and arrested multiple times for her labor organizing efforts in New York’s garment district. Her spontaneous call for a general strike mobilized thousands of female garment workers, most of them young immigrants like herself, to demand better working conditions and fair wages. The strike lasted for months and led to significant improvements in workplace safety and worker rights across the industry. Labor historians credit Lemlich’s courage with helping establish the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union as a major force in American labor, yet her name rarely appears in discussions of American labor leaders.

Benjamin Banneker: The Self-Taught Genius Who Helped Design Washington D.C.

Benjamin Banneker was a self-taught mathematician, astronomer, and surveyor who played a crucial role in designing the nation’s capital. Born to freed slaves in Maryland, Banneker taught himself advanced mathematics and astronomy using borrowed books, eventually becoming so skilled that he was appointed to the surveying team for Washington D.C. in 1791. He worked alongside Pierre L’Enfant to map out the city’s layout, and when L’Enfant abruptly quit and took his plans with him, Banneker recreated the entire design from memory. Banneker also published almanacs that contained accurate astronomical calculations, weather predictions, and tidal information, proving wrong those who claimed African Americans lacked intellectual capacity. His letter to Thomas Jefferson challenging the contradiction between slavery and the Declaration of Independence remains one of the most eloquent early arguments against racial prejudice.

Grace Hopper: The Computer Pioneer Who Invented Programming Languages

Rear Admiral Grace Hopper revolutionized computer programming by developing the first compiler, which translated human-readable code into machine language. Her work in the 1940s and 1950s laid the foundation for modern programming languages, including COBOL, which is still used in many business applications today. Hopper popularized the term “computer bug” after finding an actual moth stuck in a computer relay, and she kept the moth taped in her logbook as the first recorded computer bug. Despite her groundbreaking contributions to computer science, Hopper faced significant gender discrimination throughout her career in both academia and the military. According to the Computer History Museum, her innovations saved countless hours of programming time and made computers accessible to people without advanced mathematics training, yet she remains largely unknown outside of tech circles.

Cesar Chavez’s Right Hand: Dolores Huerta and the Fight for Farm Workers

While Cesar Chavez often gets credit as the sole leader of the farm workers’ movement, Dolores Huerta was equally instrumental in organizing migrant laborers and negotiating the first contracts that gave them basic rights. Huerta co-founded the United Farm Workers union in 1962 and developed many of the negotiating strategies that secured better wages, health benefits, and safer working conditions for agricultural workers. She coined the rallying cry “Sí, se puede” (Yes, we can), which later became a cornerstone of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. Huerta continued organizing well into her 80s, and at age 93, she remains active in fighting for workers’ rights and social justice. According to recent research from UC Davis, farm workers who benefited from Huerta’s organizing efforts saw wage increases of up to 40% and significant improvements in workplace safety, yet her contributions are often overshadowed by her male counterparts.

The Unsung Hero Behind Victory Gardens: Liberty Hyde Bailey

Liberty Hyde Bailey doesn’t just have an unusual name – he’s the forgotten agricultural scientist who made America’s World War II victory gardens possible. Bailey spent decades developing the agricultural education programs and plant varieties that enabled millions of Americans to grow their own food during wartime rationing. His work at Cornell University established the foundation for modern agricultural extension services, which taught ordinary citizens how to garden effectively. Bailey wrote over 65 books on horticulture and agriculture, making complex scientific knowledge accessible to everyday gardeners. During both world wars, his educational methods and plant breeding innovations helped American families produce an estimated 40% of the nation’s vegetables in backyard gardens, significantly supporting the war effort on the home front.

Conclusion: Why These Stories Matter Today

These forgotten heroes remind us that American history is far richer and more diverse than the handful of names we typically remember. Each of these individuals overcame significant obstacles – whether based on race, gender, class, or other barriers – to make contributions that still impact our lives today. Their stories challenge us to look beyond the traditional narratives and recognize that progress often comes from unexpected places and unlikely heroes. From the Social Security checks that protect our elderly to the computers we use daily, these forgotten Americans shaped the world we live in. What other heroes might be hiding in the margins of our history books, waiting to inspire the next generation?